Joint Submission by Wasser in Bürgerhand (Water in Citizens’ Hands) and Gemeingut in BürgerInnenhand (Common Goods in Citizen Hands) to the Questionnaire by the Special Rapporteur on the human rights to safe drinking water and sanitation for the Report to the 75th session of the UN General Assembly in 2020

1. Please describe briefly the role and responsibilities of your organization in the water and sanitation sector, particularly concerning assessment or promotion of private provision.Wasser in Bürgerhand (Water in Citizens’ Hands) is a loose German network of German water professionals and activists, engaged in local work to protect public ownership of water resources and water services. For more information see www.wasser-in-buergerhand.de.

Gemeingut in BürgerInnenhand (Common Goods in Citizens Hands) is a German non-profit association working to protect public ownership of common goods, including water. For more information see www.gemeingut.org.

Current situation and trends

1. In your view, what the role has the private sector played in the water and sanitation provision in the countries your organization works in (or at the global level)? How has this role evolved in recent decades? Please provide examples.Germany has a long tradition of public ownership of water resources as well as public, municipal water and wastewater services. (1) While public ownership is still the dominant pattern, it has been challenged in the last two decades. First, by cross-border-leasing which covered some of the most important water services such as in 2001 the Landeswasserversorgung Baden-Württemberg or the Bodenseewasserversorgung (Boden Lake water provision), then by public-private-partnerships such as in Rostock (1993-2018 100% to Eurawasser/Suez), Potsdam (1997-2000 49% to Eurawasser/Suez), Berlin (1999-2013 49,9% to RWE and Veolia, initially with Allianz), Kiel (2001 51% to TXU, 2004 to MVV Energie), Görlitz (2001 74,8% to Veolia) and Braunschweig (water 2002 74,9% to TXU, 2005 to Veolia, waste water 2005 100% to Veolia).

The liberalization of the energy market also impacted the German water as some of the public utilities responsible for energy were transformed into (partly) private corporations such as EnBW, E.on and RWE which then also own shares in water utilities, due to the historic tradition of integrated energy and water utilities in Germany. This was for example the case in Stuttgart.

However, there has also been strong resistance to privatization, with a successful referendum to oppose it in Hamburg in 2005. Furthermore, in Germany, there is a clear trend towards remunicipalisation, like in Rostock, Potsdam or Berlin.

Also at the global level we see a trend for remunicipalisation of water, as documented by http://www.remunicipalisation.org. The promises of water privatization, as they were made by international institutions such as the World Bank, have not been fulfilled in many cases, including Buenos Aires, La Paz, Cochabamba, Jakarta, Nairobi, Dar-es-Salam or Manila. An extensive list of failed privatizations can be found here: http://www.wasser-in-buergerhand.de/untersuchungen/List_of_Failed_Privatisation_Projects_in_Water_Supply_and_Sanitation-Sept_2011.pdf, many case studies can be found here: https://www.psiru.org/sector/water-and-sanitation.html.

3. Why do public authorities allow or even attract privatization of water and sanitation services? What would be the alternatives for public authorities? The German municipalities have the right to (partly) privatize water services. It is more difficult for waste-water services as they are normally legally seen as one of the core duties of a municipality (“sovereign task”, “hoheitliche Aufgabe”), but the provision in effect still can be privatized.

The financial situation of municipalities is one reason for privatization, sometimes also the expectation of superior private knowledge, which however is dubious given the long tradition of public water provision in Germany.

Another aspect is water prices. Some authorities in Germany (e.g. in Hessen) and also some official commissions (e.g. the Ewers commission in 2001) argued that private competition might lower prices. However, there is no evidence that private participation overall lowers prices, but rather the opposite, as experience in Germany. Also peer-reviewed research could not find price advantages of private water provision. (2)

And even where prices are higher, it needs to be taken into account what the service includes. In our view, the human right to water is not only about cheap water but about affordable but also sustainable and healthy water. Sustainable and healthy water also means investing into good, long-enduring pipes, minimizing pollution, renouncing to chlorination as far as possible, protecting water sources, and else, which all comes not without costs. It thus does not make sense to just compare prices as some studies have done it. Studies which take into account quality are necessary and show that public providers have a better performance than private ones. (3)

The alternative is to simply to stick to public provision and – where economies of scale are available – use public-public partnerships which are very common in Germany (so called “Zweckverband”). For a while, there was legal uncertainty, if EU procurement law allows to commission a Zweckverband without a public tender but at the moment, this is seen as “inhouse” procurement by the European Court of Justice which does not require such a tender.

4. In your view, have International Financial Institutions (IFIs) recently encouraged privatization? Could you provide concrete examples?For Germany, such an influence is not visible in recent years. However, there was recent IMF support for the privatization of the Thessaloníki and Athens water utilities (4) as well as in Portugal (5), and also World Bank support for the Lagos water privatization. (6) Also the planned introduction of water meters in Ireland as part of its austerity program might be a first step towards privatization. (7)

5. In case of economic crises, have the promotion of privatization increased? It clearly has, for example through the IMF “structural adjustment” programs such as in Greece, Portugal and Ireland (see above), or through debt. One argument for privatization was the dire fiscal situation in municipalities such as Berlin, Braunschweig or Kiel with the possibility, to gain quick money through privatization.

Private provision

6. In your experience, if the private sector is involved in provision of water and sanitation services, what process was undertaken prior to the decision to adopt this model of provision? What types of concerns have been considered in such decisions?case of economic crises, have the promotion of privatization increased? We assume that in the German privatization cases, a public tender regularly took place. However, we cannot exclude that there might have been problems with this.

Concerns by the public and sometimes the governments have been loss of public control, high salaries for management, too little investments, job losses, prices increases. However, some of this was sometimes also used as an argument in favor of privatization, e.g. management was sometimes handed over to the private minority shareholder, e.g. in Berlin and Rostock, and job cuts were seen as proof of effective management.

7. How could public authorities use the features of private providers to foster the realization of the human rights to water and sanitation (HRtWS)? Is private provision positive for the progressive realization of the human rights to water and sanitation? If yes, in which circumstances?We cannot think, at least for Germany, of any such advantage of private providers. Germany did well with with public providers.

8. How have instruments and mechanisms in place allowed the users (and non-users) to complaint and get remedy from private providers?Given that in Germany almost all of the limited cases are PPP with a major public share is rarely relevant. However, even in case of full privatization, the municipality finally remains responsible for the fulfillment of the public duties to ensure water and wastewater services. However, users might sue private providers at court. We do not know if this took place, however. Also, users might approach the Cartel Offices (Kartellämter) which then can also look at the price setting of private providers, as they have done it in various cases (partly-private providers such as in Berlin but also public ones).

9. Do private providers advocate for stronger regulation? If so, why? We are not aware of any case where private providers advocated for stronger regulation. We rather see that existing regulation, e.g. on the maintenance of pipes or on the thresholds for water pollution, is challenged by private operators. In Germany, the current rule and practice is to minimize pollution (“Minimierungsgebot”) and leakage which is not in the interest of private operators which rather want to exploit the thresholds.

10. How has been the relationship between private providers and public authorities at the local level? What are potential concerns public authorities and users face vis-à-vis private providers? We cannot judge on details of this relationship. However, the PPP contracts normally mirror concerns, e.g. lack of investments. Also, the water price or fee is a regular point of concern and conflict. In Berlin, such a conflict even led to an arbitration proceeding, resulting in an extra payment of 340 million Euros by the city of Berlin to the private companies. (8) In Estonia, a conflict even went to international arbitration. Even if it was won by the public side in 2019, it still caused massive costs for it. (9)

11. How have private providers contributed to or harmed the realization of the HRtWS? Please give examples.Rising prices make it more difficult for users to pay. In Berlin, prices rose by 35% in seven years. This increases the danger of cut-offs. While cut-offs are not specific to private providers, they seem to be more likely then. Private providers will probably also cooperate less with public authorities (e.g. if people receive social security benefits). The best examples for this effect is the UK. Cut-offs became so massive after the privatization in 1989 that the government had to massively intervene. But still, users in the UK pay exorbitant prices, as a study from 2017 demonstrated. (10)

12. What is the nature of the information available on service provision? Does it allow for the adequate accountability of private providers and public authorities? PPP contracts are regularly secret in Germany (one of a the little exceptions: Berlin water PPP, revealed after a referendum in 2011). Thus the public normally cannot assess the PPP properly, particularly in its financial consequences. Even for public bodies such as parliaments, access can be limited. E.g. in Berlin, the contracts could be only read in a kind of secret chamber, without the possibility to make copies and the right to talk about it.

13. Who monitors the performance of private providers in respect to the normative content of the HRtWS and how? Who intervenes when there are risks of human rights violations and how is it done? Who imposes penalties in case violations occur?Given that in Germany almost all of the limited cases are PPP with a major public share, this does not really apply. The general oversight over the water utilities lies with the parliaments and city councils (as owners of the public share) or with the public bodies of higher rank (Aufsichtsbehörden). Regarding prices, the cartel offices at federal and state level in recent years have partly strengthened their oversight. The Federal Cartel Office (Bundeskartellamt) issued an order to lower prices for Berlin in 2012 (11) with an extension in 2014 (12). The Länder Cartel Office (Landeskartellamt) of Baden-Württemberg issued an order to lower prices for Stuttgart in 2014 which finally resulted in an agreement with EnBW in 2015. (13)

14. What are the main challenges public authorities face regarding availability, accessibility, quality and affordability when private actors provide water and sanitation services? Please give examples.The general problem of the authorities is first to clearly define in the contract what availability etc. means. The attempt to define it leads to voluminous PPP contracts which require expensive legal advice. After the contract is entered, the authorities face a permanent problem of oversight to ensure that the contract is fulfilled.

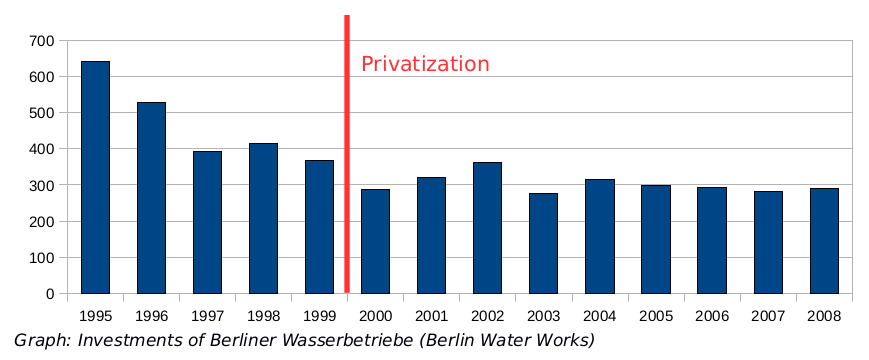

A big problem is ensuring investments, given that the private partner will not have an incentive on his own to invest properly, e.g. due to the incoherent time horizon of the regular PPP contract of 25-30 years compared to the normal life-time of a water pipe of 50-100 years. Therefore, contracts such as in Berlin prescribed investments. However, the private “partners” have still a strong incentive to minimize investments. E.g. in Berlin, the investments pre-privatization were 591 million Euros in 1996 but dropped to 298 million Euros in 2005 post-privatization (see graph). The technicians also openly admitted to lengthen maintenance intervals beyond what was prescribed. (14)

The lack of investments by private providers is demonstrated by the much lower leakage rates and higher treatment standards in countries with (mainly) public provision such as Germany, Austria or the Netherlands, compared to (mainly) privately serviced countries such as England/Wales and France. (15)

Another challenge is availability. While also public providers can cut water access in case of unpaid bills, private operators will be more inclined to cut access. In poorer countries the problem is much bigger as the problem is often the first connection to the grid. While public providers have not always done a good job on this in such countries, the attempts with private providers did not work either as promised.

Private operators are also less inclined to ensure the long-term protection of water sources. Public providers in Germany such as in Munich or Hamburg have programs to support use of organic farming around the water sources. (16) Private operators will not have any incentive to run such programs.

15. Do you know any case of corruption involving private provision of water and sanitation services? Please give the necessary details.We do not know a case in Germany. In Grenoble, outright corruption by Suez took place and – after its revelation – led to the cancellation of the tender. (17) In France, there also existed payments to municipalities by the French multinationals which were forbidden in 1995. (18) Further examples can be found on the “Water Integrity Network” website. (19)

16. Has the private sector shown more capacity to mobilize funds than the public sector? Could you please give concrete examples?We are not aware of such an example. While also public water providers have a worrisome incentive to under-invest, private providers are not a solution to this problem but exacerbate it. In Berlin, for example, the private partners RWE and Veolia had to be forced to invest by the PPP contract but the level of investment was still far below the level of investment before the PPP (see graph above). Also, the investments of private providers always are re-financed via the water prices or fees. (20)

17. In your opinion, is there power imbalance in a public-private partnership? Could you please give concrete examples of effects of this relationship?There definitely is a power imbalance: First, the writing of the contracts favors the private partners with their better (international) lawyers. Second, as soon as the PPP starts, the public side can be black-mailed with the danger of the bankruptcy of the private partner and the ensuing need to ensure the provision of the services or at least financially support the private partner. This is why in Germany, PPP contracts often are amended later on, e.g. the Berlin water was amended several times in the interest of the private partners. This even included passages of the PPP contract which was ruled not to be constitutional by the Constitutional Court of Berlin (e.g. on a “risk premium” of 2% included in the original PPP contract). (21) Also the water fees in Berlin were always adjusted to serve the interest of the private partners which led to a steep increase of the fees.

The public side also seems to be unable to stop the sell of shares on the private side. E.g., in Rostock, Suez sold its subsidiary Eurawasser to Remondis without any influence of the city.

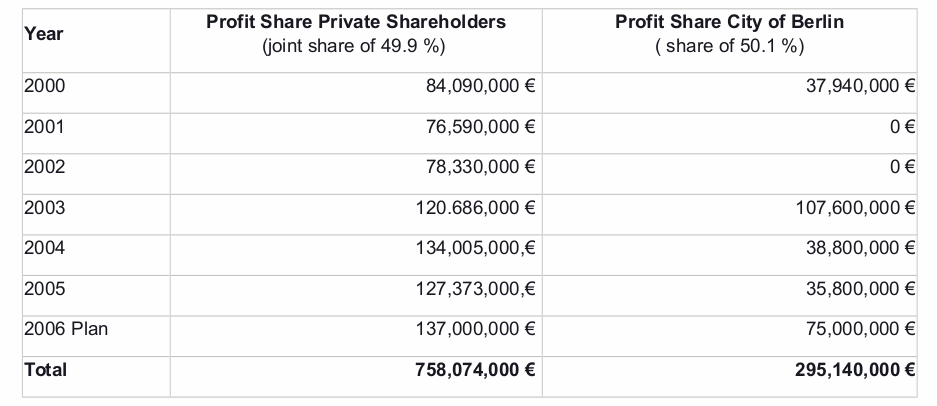

The imbalance also lies in profit guarantees that are often enshrined in PPP contracts. In Berlin, this lead to to a massive bias towards the private (minority) partners when it came to the profit distribution, as shown in the following table (which even covers the first six years after the privatization):

18. When there is private participation in the water and sanitation sector, to what extent the private actor brings its own financial resources to the service? All financial resources invested by the private providers are recovered by fees paid by citizens, so there is no additional resources available from the citizens’ point of view. (22)

Remunicipalisation

19. Have you studied any case of remunicipalization? Why and how has it occurred? What types of difficulties has the public authority faced to establish the new municipal provider? Please, provide details of those processes. There is a clear trend for remunicipalisation in the German water sector. (23) The most important remunicipalisations in Germany are Rostock (24), Potsdam (25), and Berlin (26). In Potsdam and Rostock, conflicts between the public side and the private companies led to an cancellation of the PPP contract, in Rostock with the regular expiration, in Potsdam with an early cancellation. In Berlin, there was pronounced public pressure to end the PPP due to rising water prices, loss of public influence, and other problems. This led to a referendum in 2011 in which 98% of the participating citizens voted for the publication of the PPP contract. This finally triggered the remunicipalization two years later.

In Potsdam, the cancellation of the contract with the following compensation (for the whole contract durance) led to the highest water prices in any German city, in Berlin, the cancellation also was very expensive due to the financial compensation. This shows how difficult it is to get out of a PPP contract once it is entered.

In Stuttgart, remunicipalization has been decided by the City Council already in 2010. However, the implementation is still pending as there was no agreement with the partly-private partner EnBW about the sale price for the water grid. (27) This also shows one important danger of privatization because the hand-over of assets is not clearly ruled in the PPP contract.

Footnotes

(1) For an overview see https://www.bdew.de/media/documents/20150625_Profile-German-Water-Sector-2015.pdf.

(2) See for example https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46508720_Is_Private_Production_of_Public_Services_Cheaper_Than_Public_Production_A_Meta-Regression_Analysis_of_Solid_Waste_and_Water_Services‚.

(3) See e.g. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290456699_Comparison_of_European_water_and_wastewater_prices_Part_1_Drinking_water and https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290279521_Comparison_of_European_water_and_wastewater_prices_Part_2_Wastewater

(4) https://journals.euser.org/files/articles/ejms_may_aug_17/Maria.pdf

(7) https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-29798331

(13) https://www.enbw.com/unternehmen/presse/pressemitteilungen/presse-detailseite_109120.html

(14) See the movie „Wasser unterm Hammer“, https://onlinefilm.org/de_DE/film/23736.

(15) See e.g. the figures in the VEWA study, https://prezi.com/jxwna6vfzu9z/vewa-comparison-of-european-water-and-wastewater-prices/?utm_campaign=share&utm_medium=copy.

(16) See examples in the movie „Water Makes Money“, e.g. for Braunschweig, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=peaG9HNJ4JQ.

(17) https://www.ades-grenoble.org/ades/dossiers/eau/water.html

(18) https://monde-diplomatique.de/artikel/!636104

(19) https://www.waterintegritynetwork.net/2015/03/11/what-is-corruption-in-the-water-sector

(20) See examples in the movie „Water Makes Money“, e.g. for Braunschweig, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=peaG9HNJ4JQ.

(21) https://openjur.de/u/270712.html

(22) See examples in the movie „Water Makes Money“, e.g. for Braunschweig, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=peaG9HNJ4JQ.

(23) For an overview see https://www.municipalservicesproject.org/userfiles/OurPublicWaterFuture_Chapter_three.pdf

(24) For an overview see https://www.municipalservicesproject.org/userfiles/OurPublicWaterFuture_Chapter_three.pdf

(25) For more information see http://www.remunicipalisation.org/#case_Potsdam and https://www.municipalservicesproject.org/sites/municipalservicesproject.org/files/Hachfeld-2008-Remunicipalisation_of_Water_Potsdam-Grenoble.pdf

(26) For more information see http://www.remunicipalisation.org/#case_Berlin and https://www.tni.org/en/article/remunicipalisation-in-berlin-after-the-buy-back

(27) For more information see http://www.remunicipalisation.org/#case_Stuttgart and https://www.euwid-wasser.de/news/politik/einzelansicht/Artikel/stuttgart-keine-einigung-ueber-rueckkauf-des-wassernetzes.html